The future of robotics: Utopia or Distopia?

From Frankenstein to Ex-Machina, we’ve long been fascinated by the idea of scientifically creating life-forms that not only look like us, but can also think like us, with the ultimate goal of developing emotional intelligence.

We seek the idea of creating something that we can mould to suit our needs and desires, but without losing the connection which enables us to relate to it. This fantasy, which has been represented many times in films and books, is now becoming a reality. But is it something we should even be considering?

Should robots act and look like people?

During the 2016 Web Summit, Ben Goertzel from Hanson Robotics and Andra Keay from Silicon Valley Robotics had a debate on the ethical implications surrounding the topic, ‘Robots should look and act like people’. Is what’s achievable the right thing to do? Where are the limits when we start producing machines that could potentially have feelings? Where is the line between human and machine?

Ben Goertzel positioned himself in favour of robots looking like humans, arguing that this could enable them to learn from people and develop values and emotions. In his view, this could help the ‘super intelligent’ to become friendly, and to develop better relationships with humans. The aim would be to give people the emotional experience they crave. Goertzel argued that if robots could act and feel like humans, surely they could understand us better and hence serve us better. They could mimic social interactions and anticipate human expectations.

Many of you will remember the film ‘Bicentennial Man’ starring Robin Williams as a robot who wants to become a human. The film explores themes of humanity, slavery, prejudice, maturity, freedom, love and mortality. In the movie, Andrew is a robot that starts life as a machine, acting accordingly. Andrew is introduced into a family as a housekeeping robot, and they all soon discover that he is intelligent and capable of emotion and learning.

Throughout the movie, we see Andrew’s attempts to become a fully functioning human on both the outside and the inside. In his pursuit, he ends up successfully using technology to age and, ultimately, to die. Now, what about the other way around? Would humans want to become machines in an attempt to keep improving and even cheat death?

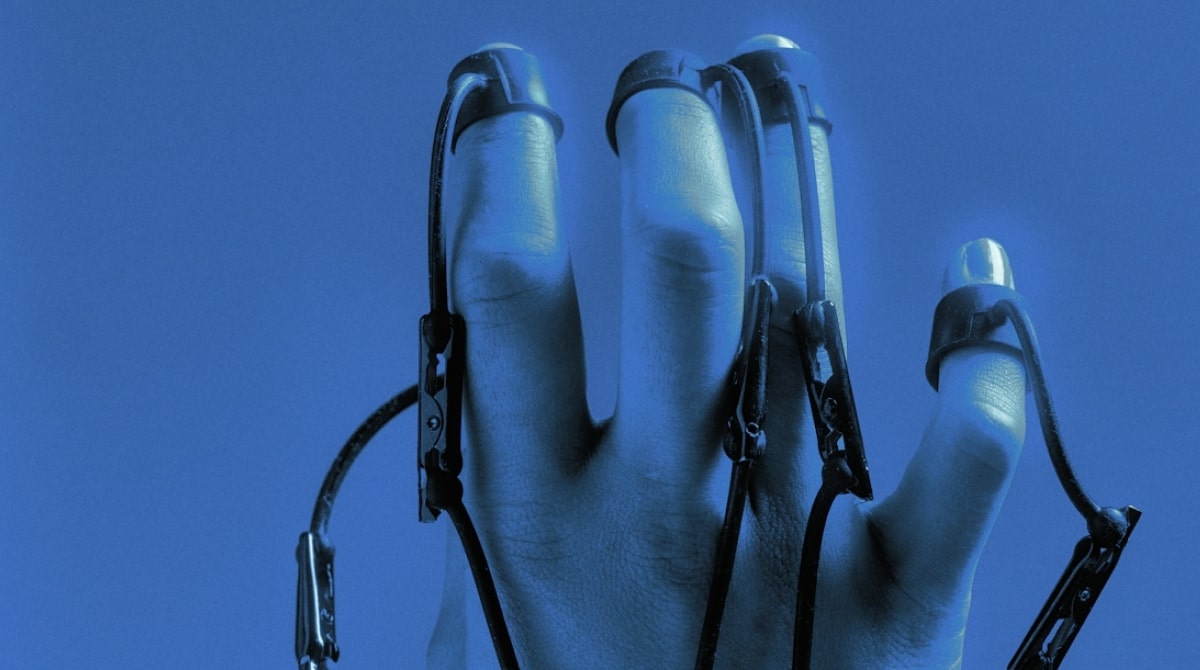

There have already been significant advances in creating bionic body parts such as hands and legs, and medical trials are underway to explore ways to repair, refurbish or replace human organs that have been damaged by chronic disease and traumatic injury. 3-D printing technology is starting to be used to build bio-artificial body parts and organs. But what about the brain?

Will humans become hybrids?

In 2015, inventor and director of engineering at Google, Ray Kurzweil, said that in the 2030s humans’ brains will be helped out by nanobot implants that will turn us into ‘hybrids’. The implants will connect us to the cloud, allowing us to pull information from the internet. Information will be sent over cloud networks, letting us back-up our own brains. He thinks that, “we’re going to gradually merge and enhance ourselves…that’s the nature of being human — we transcend our limitations.”

Our thinking would improve in time as the cloud that our brain’s access becomes more advanced. This means that even though we will start by having a “hybrid of biological and non-biological thinking”, as we move into the 2040s, most of our thinking will be non-biological. This is in-line with Ben Goertzel’s ideas. After all, and according to his own words, humans are robots at some level and both humans and machines are part of the same growing universe.

If Kurzweil’s predictions are correct, we’re heading for a new hybrid society in the next couple of decades. It currently feels like a Philip K Dick storyline, what with humans becoming machines, and machines becoming humans. The concern is, are we heading for a dystopia?

The ethical argument

Andra Keay certainly does not believe that this ‘hybrid society’ is feasible in the foreseeable future and regards it as highly unethical. During her speech, she raised concerns about robots looking like humans and acting as mechanised slaves. She argued that this would enable us to indulge in bad behaviour without any repercussion. This could lead to objectification and bullying, reaffirming behaviours that would be unacceptable otherwise. She also anticipated issues that had to do with stereotypes, racism and the potential to deceive.

If we take a look at the latest human-like robots such as intelligent droid Jia Jia or Erica, we can identify a tendency to perpetuate the stereotypes in appearance and behaviour that we see in human society. This means that females are beautiful and delicate and males strong. A female robot would typically nurse and take care of people, whereas male robots would guard and patrol. There are no diverse representative robots either.

Ryan Calo, A. Michael Froomkin and Ian Kerr explore this in their book ‘Robot Law’. The books states that trying to imitate human appearance can result in designing robots based on stereotypical assumptions. Furthermore, complex notions of race and gender can be reduced to simplistic views of how men and women from different races should look and behave.

The field of robotics develops technology within a social context, so it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume that some values and interests could be installed in the way robots are developed, which could mean that making robots look like humans could have the potential to reproduce, and even aggravate, inequalities in society.

The potential of deceiving people and taking advantage of the ease they could have when interacting with human-like robots for commercial purposes should also be considered. Who is behind that friendly, attractive female robot trying to engage in conversation? Where does the data go and to what purpose?

As for slavery, if we were to create a robot so similar to a human in appearance, intelligence and emotions, with the ability to experiment with human-like interactions, would it be right to make them serve us? Would it be ethical to objectify them and make them our property? The concern of making compliant machines look like people could certainly lead into validating slavery again.

The answer to a more fulfilling life?

If we go back to machines simply looking like machines, then there are no issues with having them at our service, helping us improve the way we do things.

Jacque Fresco with his Venus Project runs away from the idea of human-like robots as well. He dreams of a connected society where machines are just machines, albeit super-intelligent ones that can undertake jobs and duties in a more efficient way.

Engineers would design, develop and improve machines that could manage our planet’s resources, constantly communicating with other machines around the world. He believes they would run a much more efficient system. By taking away the most mundane tasks, they would free up our time and enable us to focus on what’s really important to us: being happy and living a fulfilling life as humans.

Are we on the verge of a society where humans and machines are indistinguishable from each other? Or are we heading towards a connected world where robots are just machines that make our lives easier? Only time will tell.

More Insights?

View all InsightsQuestions?

Global SVP Technology & Engineering